President Barak Obama recently gave an interview in which he

purported to speak to parents in Central America. He warned parents not to send their children on the long and

dangerous journey across Mexico to the United States. He

said, “do not send your children to the borders. If they do make it, they'll get sent back. More importantly,

they may not make it.” His

comments were spurred by a rapid increase in the number of unaccompanied minors

arriving without visas at the Mexico-US border. Because children are involved this trend has attracted

massive media attention and injected even more emotion into the turbulent,

cynical, and exasperating topic of immigration to the United States.

The

most disheartening aspect of the President’s comments is that they completely

dehumanize the people living in Central America. By chiding the families of minors arriving without governmental

permission the President makes it appear as if they are bad parents. Who would send their young child alone

across hostile terrain rife with rapists, gangs and coyotes? Even worse,

while the President imputes bad parenting to these families, political figures

on the other side frame these people as devious manipulators, risking their

children to steal a slice of the American pie. Despite the vast breadth of human experience, both of these

characterizations must be overwhelmingly wrong. The sad fact is that what is occurring is natural,

understandable and predictable.

The

situation in Central America is desperate. How desperate? Desperate enough to make sending your child

alone to the United States a reasonable option. The utter lack of empathy with this reality demonstrated by

political figures in the US, including the President, is disgraceful. The well-deserved popular image of the

region is of poverty, insecurity, and political instability. The wider world has become accustomed

to accepting the suffering and desperation implicit in these sanitized

terms. Specifically, we have accepted that they have accepted their suffering and

desperation. What this current

“crisis” lays bare is the fact that we are not prepared for those we have resigned to their fate to do something about it. As Harper Lee wrote in To Kill a

Mockingbird, “you never really know a man until you understand things from

his point of view, until you climb into his skin and walk around in it.” Before any more politicians admonish

parents in Central America, they are cordially invited to spend a week living

in the neighborhoods of Tegucigalpa or San Salvador where these children grew

up.

Political

hyperbole is nothing unusual and does not merit much discussion, but Mr.

Obama’s declaration that “they will be sent back” underscores a real and

serious problem; the near total lack of adequate tools for coping with human

migration in the 21st century. Worse, the government’s plan to use “voluntary

departure” to legally bind minors, cut off many legitimate asylum claims and

repatriate these children as quickly as possible, undermines the inadequate

rules already in place. Ignoring

these issues for now, a wider lens serves to give perspective on the crumbling

global migration regime.

At

the heart of the problem are antiquated and disjointed asylum laws and treaties. The most fundamental flaw is the

category of asylum itself. The

distinction between “refugees,” who theoretically enjoy the protections of

asylum, and “economic migrants,” who do not, is unrealistic and intellectually

dishonest. Most people with

economic opportunities, adequate resources and hopeful futures do not engage in

war or persecution.

Compartmentalizing and separating the cause (poverty) and effect

(refugees) of human experience is neither prudent nor useful. Splitting “economic” and “humanitarian”

reasons for permitting migration causes perverse results. Economic migrants can be turned back

with a clear conscience because society is meeting its moral obligations by

leaving open asylum as an avenue for truly deserving migrants. At the same time, access to asylum is

continuously narrowed because of fears that economic migrants are infiltrating

and abusing the system.

Ultimately, this line of reasoning arrives at a moral and rational

paradox. The children arriving at

the Mexico-US border are living and breathing this

paradox. A young person fleeing

violence and poverty is a “deserving” migrant within the logic of asylum. But despite their age, these people are

also seeking to improve their economic well-being and thus the government is

left with no good options.

The

second major problem highlighted by the current media attention is the use of

resources. President Obama asked

Congress to allocate $3.7 billion to help deal with the costs of detaining,

processing and deporting migrant youth.

Nearly a third of that money would go to Immigration and Customs

Enforcement (ICE) to facilitate detection and detention. Consider the $100 million spent

by the US government to produce an ad

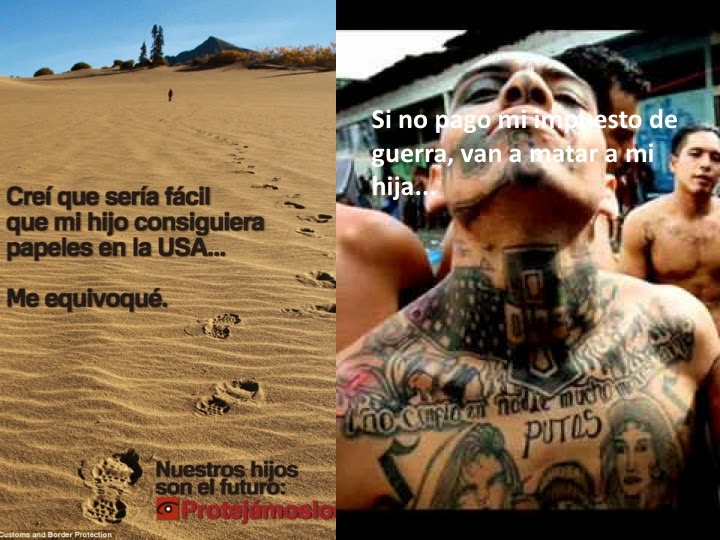

campaign to try to dissuade parents from sending their children. The imagery is useful. An example of the ad campaign shows

lonely footsteps across the sands of a deadly desert. But this should be juxtaposed to a shot of a tattooed Mara

who knows where you and your family live, work, and go to school. The banner can read, “if you piss him

off, there’s only a 2%

chance of your murder being solved.”

With those odds the desert doesn’t seem like such a bad choice. In tragic parallel to the extremely

relevant Drug War, any reeducation funds would be much better spent at home

than abroad. Perhaps $100 million

could put a dent in damaging xenophobic fear and misinformation used by politicians

and reverberated in the media.

Simply put, resources diverted to fences, guards, drones and hapless ad

campaigns compound the problem by not only failing to address the underlying

issue, but costing taxpayers and incurring more negative sentiment. Unfortunately, the misallocation of

resources is a response to the failed international instruments supposedly

governing international human migration.

The

cycle persists because until proper international treaties are agreed to and

implemented, societies must bear the costs of the negative externalities. In concrete terms, the United States

and its taxpayers must pay for the asylum of possibly hundreds of thousands of

people. Obviously, the government

will do everything in its power to avoid such expense and so the cost is thrust

back. Unfortunately, there is no

capable sovereign on the other side and so the cost is laid on the migrants,

the children, and their families.

None of these scenarios are sustainable. It is as unreasonable to expect the US taxpayer to foot an

enormous asylum processing cost as it is to expect a poor person in Honduras to

live under the dominion of armed youth in street gangs. On the ground the US has gained a

pyrrhic victory by avoiding the cost of granting mass asylum, but is still

spending massive sums to detain, process, and return migrants. In economic terms, the current

situation is unsustainable.

Global

warming is an apt analogy. Governments

across the globe are required to pay for the increasing costs associated with

the negative externalities of climate change. Floods, fires, and droughts are drawing more government

attention and resources. However,

because sandbags and firefighters only treat the effects of global warming, the

government spending has no long-term beneficial impact, other than direct

employment (not to be discounted in the immigration context). The costs associated with the failing

global migration regime are not only monetary.

Perhaps political costs are the

most relevant when trying to understand President Obama’s recent remarks on

parenting. It is unclear whether

politicians gin up xenophobia and racism for their political purposes and thus

perpetuate them, or if politicians are merely responding to inherent

in-group/out-group thinking that has followed humanity out of the jungle. Most likely it is a mix of the

two. Regardless, politicians, who

purport to lead societies, are the principle obstacles to meaningful

improvements in the international migration regime. Of course politicians make ready scapegoats, but the lack of

courage that allows racist and xenophobic policies to persist in the form of

restrictionist immigration policies and Golden-Dawn-esque

rallies calls into question the political system itself. The purpose of government should be to

promote the expanding and inclusive well-fare of all, not to drive a zero-sum

game invented only to perpetuate the political class in its position of

authority.

There

is no easy solution. As we watch

children being detained and sent home for being too poor to afford a visa, or

people in leaky boats being pushed back in open waters, it is not hard to lose

faith. Our sciences are not

sufficiently integrated to understand the marco-to-micro systems at work, but

something can be said for having a start

here.