The setting of migration policy

is, and has been in modern times, a function of national governments. The control of movement of people into (and less

frequently out of) national territory has been seen as a prerogative of the

sovereign. Even in federalized

states such as the United States or Argentina, migration policy rests with the

national government. This is a

product of internal power dynamics between the federal and state governments as

much as a by-product of the Westphalian system of independent sovereign

states. However, there has been a

growing global discussion questioning this status quo. Consider the recent upsurge in

state-level immigration laws enacted in the United States. According to the Immigration

Policy Center, in 2006, 570 state-level immigration bills were introduced;

84 laws were enacted and 12 resolutions were adopted. However, in the first quarter of 2010, 1,180 immigration

bills were introduced; 107 laws were enacted, and 87 resolutions were adopted. At the local level in the United

States, the emergence of the “sanctuary-city” reflects another attempt to

devolve immigration policy away from the national epicenter. Both Canada and Australia have regional

(that is, sub-national) immigration programs. For example, in Canada all of the country’s provinces may nominate

a certain number of people for visas each year. This trend reflects the fact that local and regional

governments are the most affected by the costs and benefits of immigration. The current national-level policies

often fail to reflect these specific needs or are too slow in responding.

At the same time, regional

(supra-national) integration continues to trundle along, glacially assembling

blocs of countries along geographic or ideological criteria. The most famous scheme is the European

Union, but there are a plethora of such integration plans with varying goals

and levels of institutionalization.

Regional integration can take the form of free trade areas such as NAFTA

or customs unions like MERCOSUR or regional trade blocs such as ASEAN or the

African Union. Through a process

denominated “spillover” by Philippe

Schmitter, integration schemes tend naturally to grow beyond their initial

purpose to encompass more policy areas.

The European Union began in the 1950’s as a coal and iron agreement

between France and Germany. More

recently the customs union between Brazil, Argentina, Uruguay, Paraguay and

Venezuela (MERCOSUR) has expanded into migration policy and lead to the

establishment of a special visa for member citizens. Given this hypothesis of integration spillover, migration

policy will increasingly grace the agendas of such integration bodies. For example, the European Commission is

currently

considering the creation of a Commissioner for Migration.

As local and sub-national actors

create immigration policies to respond to their real world needs and

supra-national integration actors are forced to respond to the transnational

impacts of human migration, the Westfalian nation-state is stuck in the

middle. What is the appropriate

balance? Where can effective and

coordinated immigration policies be incubated? Unfortunately, the answer must be a mix of all three levels:

the micro, mezzo, and macro. This

will require a level of information sharing and communication never before seen

in human governance. It is a

challenge that confronts many policy areas, not just migration. The increasing global connectivity of

people, as well as the growing agency of the individual, makes sensible local,

national, and supra-national policymaking essential. There is some hope that information technology can offer

solutions to this gargantuan problem, but these tools are by no means a

panacea. Further complicating the

task are political tug-of-wars between policymakers at each level, all trying

to maximize their political clout and relevance. While local and supra-national actors step into the breach of

policy making around immigration, the nation-state will not lightly divest

itself of such a powerful and symbolic policy area. The benefits of coordinated and inclusive migration policies

are not hard to imagine, however neither are the costs of establishing such a

system.

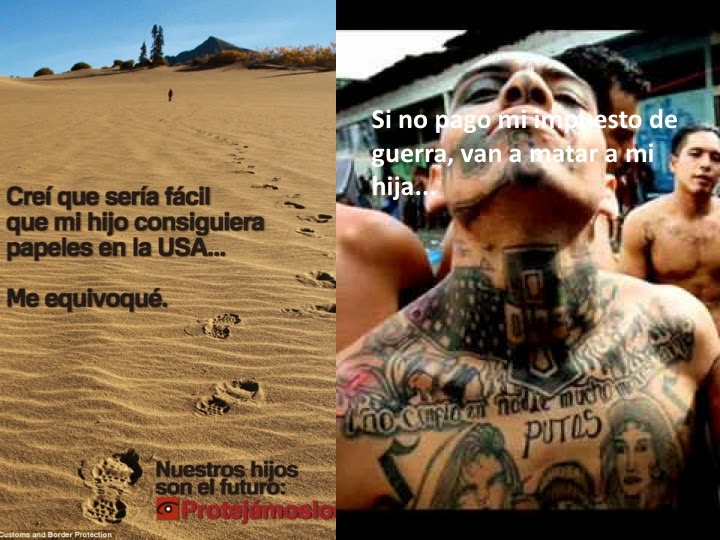

Like most political endeavors, change is unlikely until the costs of inaction so clearly outweigh the costs of action that policy makers are essentially forced to move. The current trend seems to indicate that we as a species are headed in such a direction. Global population continues to increase and migration-related policy issues such as public health and environmental protection are increasingly gaining political salience. Global inequality and armed conflicts add pressure to the mix. The need for cogent, multi-level migration policies will grow ever more apparent, even as reactionary and xenophobic responses also grow. Fortunately, sensible migration policy can only be achieved thought true and representative democracy, thus the struggle for such migration policies is also the struggle for renewed democracy across the globe.

Like most political endeavors, change is unlikely until the costs of inaction so clearly outweigh the costs of action that policy makers are essentially forced to move. The current trend seems to indicate that we as a species are headed in such a direction. Global population continues to increase and migration-related policy issues such as public health and environmental protection are increasingly gaining political salience. Global inequality and armed conflicts add pressure to the mix. The need for cogent, multi-level migration policies will grow ever more apparent, even as reactionary and xenophobic responses also grow. Fortunately, sensible migration policy can only be achieved thought true and representative democracy, thus the struggle for such migration policies is also the struggle for renewed democracy across the globe.